Making matzo at home brings with it an unusual challenge: because the goal of eating matzo is to remember the sacrifices our forebears made, it’s not really supposed to be enjoyable. Store-bought matzo, if made appropriately, should leave one with the approximate sensation of having eaten crisp cardboard made out of dust. It’s shattery. It’s white. And it’s very, very plain.

The problem is, I usually avoid boxed matzo. I don’t steer clear because of the taste. I skip it because it’s just the type of white-flour product—plain, slightly sweet, and likely quite processed—that makes me feel crummy. Gluten-free matzo are commercially available, but they’re heinously expensive. And unlike regular boxed matzo, which often come in various flavors, gluten-free matzo are (in stores near me) always naked.

I lined up my matzo musts: First, I wanted my crackers to taste like an everything bagel, with a smattering of seeds. Second, I wanted to avoid grains, lest someone question my devotion to Ashkenazi Judaism (to which I am not even slightly devoted), practitioners of which typically avoid all grains during the holiday. Third, the matzo had to be disappointing in some way. There’s no point in making a cracker that doesn’t taste like suffering if you’re going to eat it for a week straight while pretending to suffer. I couldn’t call it matzo if it didn’t leave me needing a glass of wine, or at the very least, water.

“This can’t be called matzo,” said J, a high school friend who’s recently moved to Seattle. “It tastes too good.” She was munching on a cracker I’d made from a mixture of almond, coconut, and garbanzo bean flours—a mixture sprinkled with poppy, sesame, and caraway seed, crunchy sea salt, and dried onion flakes, then baked until the edges curled up. We dipped the crackers in hummus, pondered, and ate more.

“I’m no expert, but there is no way these are matzo,” she repeated. She was right. I wasn’t feeling even the least bit guilty about having a nice life, or peaceful surroundings, or leavened bread–not to mention making a cracker that took longer than the “official” limit of 18 minutes to make. I was feeling guilty about planning to not eat the same terrible cardboard everyone else planned on eating.

“They’re a cross between socca and a graham cracker,” declared Jim. And he was right. We actually enjoyed them.

The next day in the car, I started preparing Graham for what will probably be the first Passover dinner he will actually understand. I talked about how Jewish people take the holiday as a moment to slow down and appreciate what they have. About how we eat certain foods to celebrate the season, and how we always leave the door open, in part to welcome in anyone who might stop by with a hungry stomach.

“Mom, what does ‘Jewish’ mean?” he asked.

Right. I’d forgotten the basics. I’m a secular Jew: I’m Jewish by tradition and by generational duty, but not by proactive practice. We don’t talk very much about religion in our house.

“Jewish means something different to everyone,” I said carefully. I went on to give a very brief, very bad explanation of how religions differ, and how everyone needs to find out for themselves what practice works best for them, if any. Our conversation fizzled, and I cursed myself for being so unprepared.

Then, when we got home, I got an idea.

“Here,” I said. I handed him a matzo. “This is what Jewish tastes like to me.”

He refused to taste it. And in that moment—feeling guilty for giving the matzo too much flavor, and for failing to teach my son about my family’s past practices, and for realizing he had zero concept of what was going to happen later in the week at Passover dinner—I realized I could call it matzo. I’d suffered enough.

Eat it smeared with additional guilt.

Gluten-Free Everything Matzo Crackers (PDF)

Gluten-Free Everything Matzo Crackers

Made with a combination of garbanzo, almond, and coconut flours, these crackers have a texture slightly crisper than graham crackers, with a much more savory flavor. Topped with a smattering of the seeds you might find on an everything bagel—plus caraway, a favorite of mine—they make a good substitute for any cracker you’d use for hummus, cheese, or tuna salad. Put them on the Passover plate, if you feel like it—but be warned that they’re more flavorful than traditional matzo!

Look for minced dried onion in the spice section of your local grocery store.

Time: 35 minutes active time

Makes about 6 servings

2 teaspoons poppy seed

2 teaspoons white sesame seed

2 teaspoons dried caraway seed, roughly chopped

2 teaspoons minced dried onion

1 1/2 teaspoons crunchy sea salt, crushed til fine if large

1 cup (100 grams) potato starch

1/2 cup (60 grams) coconut flour

1/2 cup (50 grams) almond flour

1/2 cup (50 grams) garbanzo bean flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

1/2 teaspoon baking soda

Pinch kosher salt

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil, plus more for brushing

1/4 cup warm water

2 large eggs, blended

Preheat the oven to 450 degrees F, and space two racks evenly in the oven. Cut two pieces of parchment paper to fit the flat parts of two large (such as 12-by-17-inch) baking sheets. (You’ll roll the cracker dough out between the two pieces of parchment, so they need to be the same size. If you don’t have two baking sheets of the same size, just pick one, cut out two pieces of parchment to fit it, and bake the crackers in two batches.)

In a small bowl, blend the poppy, sesame, and caraway seed with the onion and sea salt with a spoon until well mixed. Set aside.

In the work bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, stir together the potato starch, coconut flour, almond flour, garbanzo bean flour, baking soda, baking powder, and kosher salt just to blend. With the machine on low speed, add the oil, water, and egg. Increase speed to medium and blend for one minute, until crumbly. The mixture should clump together when you press a handful between your palm and fingers.

Pat the dough into a ball, then split it roughly in half. Place one of the parchment sheets on a clean work surface, then add half the dough. Top with the other sheet of parchment and roll the dough as thin as possible without breaking it; it should almost reach the edges of the parchment. (The goal is to make one giant cracker about the size of a baking sheet with each half of the dough.)

Brush one baking sheet with olive oil. Peel the top sheet of parchment off the rolled-out dough, then carefully invert the dough onto the prepared baking sheet, paper side up. Peel off the remaining piece of paper, and brush the dough with more olive oil.

Repeat the process with the remaining dough, using the same parchment paper. Scatter the spice mixture over both pieces of oiled dough, then pat the spices in with your hands so they stick. (If you’d like a more matzo-like look, use a fork or a rolling docking tool to poke small holes all over the dough.)

Bake the matzo for 5 minutes. Rotate the pans front to back and top to bottom, and bake another 5 to 7 minutes, or until the matzo is well browned on all edges and begins to curl up and off the pan. Transfer the crackers immediately to cooling racks and let cool for at least 30 minutes before breaking into pieces and serving.

Store any unused crackers in an airtight container, up to 3 days.

If you’ve followed the Uncle Josh Haggadah Project over the last five years, never fear, there is a 2015 edition. This year, it focuses on Montana, and was written in conjunction with our sister. Click here for the PDF of the 2015 Haggadah.

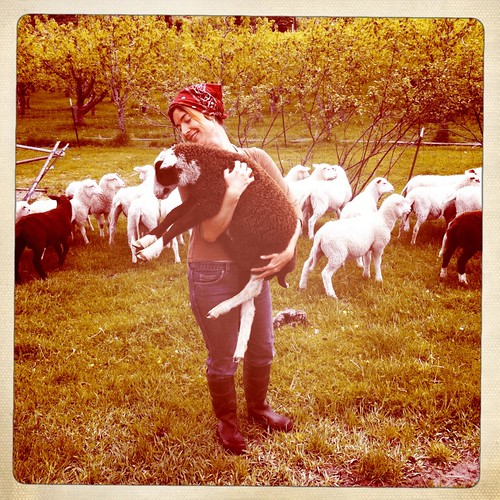

What We Don’t Eat

It’s always been hard to judge Bromley’s misery properly, because she’s been a miserable, hateful sort of creature since the beginning. She’s almost never affectionate, and pouts constantly, and whines if she smells food but doesn’t get to eat it (which, in my line of work, happens often). She hates rain and children and men with beards, and feet without shoes on them, and people touching her feet, or her head. She’s the cranky neighbor and the crazy lady on the corner and the mean librarian, all rolled into an aging, stinky, always-hungry beast. As we talked about putting her down, my husband and I stared guiltily at each other, each thinking our own version of the times we’d wished aloud that she’d just hurry up and die already, so we didn’t have to clean up the remnants of the individually-packaged kids’ juice boxes she’d opened with her big maw and strewn across the living room rug, or wonder how she’d gotten to the shoulder-height bag of cat food. Thinking about how different she was from the dog we thought we were getting, almost 13 years ago.

Bromley comes from good eaters. When we arrived to pick her up for the very first time, her mother was counter surfing. We should have known then.

“SYRI,” bellowed Syringa’s owner, before Siri became a terrible name for a dog. The red bell pepper Syri had claimed from the cutting board dropped to the floor. Innocent eyes begged forgiveness.

From the moment we got Bromley home, she was the same kind of scavenger, ripping open entire bags of sugar, stealing donuts off the counter, sneaking bites of steak directly from a hot grill, and generally failing to understand that the kitchen counters weren’t dog domain. She learned to stand in the center of the kitchen and not move, ever, interrupting the so-called kitchen triangle so effectively that we could never get from the refrigerator to the stove or the stove to the sink without running into her unmoving bulk. When we scolded her, she looked up at us with what we soon came to call “filet eyes.” She knew she was beautiful from a very young age, which didn’t help.

Outside the kitchen, she was cold and loveless. She refused to be petted. She hated being touched. She generally hated other dogs, too. No matter how much time and money we spent training her, she only paid attention to us if we had food in hand or if she was seated on some sort of couch. For years, we joked about giving her away.

But about two months ago, our big Rhodesian Ridgeback plum stopped eating. We’d taken her in to have her various old lady lumps inspected, but until then, while she was partially deaf and blind and starting to lose her barking voice, there hadn’t been anything actually wrong with her. Not eating seemed like a giant red flag.

That same week, she fell up the stairs. She was ambling up them after eating her breakfast in the laundry room downstairs, and her back paws slipped out behind her on the polished wood, just a stair or two from the top. I heard a yelp and a thunk, as all 85 pounds of her hit the floor, and ran to find her stuck, chest and front paws prostrate on the top landing, with the back paws pads-up behind her. I had to lift up her backside so she could gain enough traction to finish the job. She was very embarrassed.

“I’d say 90 percent of our clients let their dogs live too long,” said the admin at Bromley’s vet, when I called to ask how one knows when it’s time to put her dog down. “We see a lot of dogs that suffer for way too long. And not eating is generally not a good sign.”

I dropped my phone, collapsed into the bed beside my snoring hound, and sobbed into her fur until she wiggled away, grossed out by my storm of affection. That afternoon, I brought her in for a check-up, but again, there wasn’t a single definable something wrong. The vet insisted it was our choice, but made sad little nods and pursed her lips a lot.

And so we went into discussions, round and around, trying to decide whether it’s better to wait until a dog shows definite signs of the end-of-life kind of aging before putting her out of her misery, or to have her anesthetized before anything tragic happens, and save her the pain. I bought her lovely hunks of beef leg bones to chew and thought about what we’d do, if we gave her a day of her favorite things before it was all over. We’d take her to the beach, of course. I started planning a steak dinner goodbye party in my head.

Because she’s the dog we got, we have loved her. And because we were heading out of town, and because a few days after seeing the vet she simply started eating again, we didn’t put her down.

Instead, we gave Bromley to my husband’s parents for two weeks, and left for our spring break road trip, hoping she’d be there when we returned, and that no one else would have to do what we hadn’t been ready to do ourselves. And the first day they had her, they wound up in the emergency room.

It was an abscess in her foot that had clearly been there for a long time, said the ER vet, and, later, our own vet. Weeks, maybe, or longer. It was likely the sign of bone cancer or a deep bone infection, they thought, but just in case, they’d treat it like a random foot infection. They cleaned it and drained it, and put in stitches, which fell out as the wound worsened, and put in staples, which fell out also, and put in more staples. My in-laws shepherded her through multiple rounds of pain medications and antibiotics, and Bromley became famous with all the vet techs. When we returned, my in-laws had had the patient in their home for two full weeks. They’d covered their rugs with puppy training pads to prevent the blood from Bromley’s wound from staining everything. The injured leg was wrapped in a big purple bandage more appropriate for a 12-year-old girl than a 12-year-old dog.

And when we came home, Bromley seemed upbeat. She was eating normally. She seemed happy to see us, even. We took her in to get her staples out, three weeks after the ER visit, and the vet leveled us with her steady, sweet gaze.

“There is a chance that it could just be a tissue infection,” she said defensively. “But honestly, I’d say I’m 99 percent certain it’s either a cancer or a deeper bone infection.” She recommended an X-ray, which would tell us which it was. The cancer could theoretically be treated with amputation, and a bone infection would require a month or so of IV antibiotics.

Jim and I looked at each other. We knew we couldn’t amputate one back leg of a dog who could no longer reliably stand on two. And since every vet visit left her shaking and bereft, sending her to a dog hospital for a month would be devastating to her. We told the vet we didn’t need the X-ray and left, chewing on her warning that sometimes, bone cancers can take over in a matter of weeks.

At home, we spoiled her rotten. I bought fat, fresh spot prawns for grilling, and we ate them, but saved all the shells for her dinner bowl. I let her eat corn straight off the cob, in little bites. I fed her the crusts from Graham’s lunchtime sandwiches. We committed to buying canned dog food, which is outrageously expensive, and smells not unlike excellent pâté.

A few days later, my husband left on a business trip. I took Bromley in for her final foot check-up, and the vet declared it healed—healed better, in fact, than she had thought it might. Bromley wove her bumpy body between my legs as well as she could, like a toddler burying her head in her mother’s legs to hide. It was as if faced with her final moments, she’d decided she did actually have some love to share. As I was leaving, I suddenly decided I should ask to have the foot X-rayed. Off went Bromley, shaking terribly, with the perennially peppy vet, who seemed to pity me because I was about to learn the method nature had chosen for my dog’s execution.

But the vet came back with a funny look on her face.

“I’m happy to tell you that I think I was wrong,” she said. “I can’t find anything. Her foot looks completely normal.”

“Normal?” I asked, surprised and almost crestfallen. “Let me see.”

I couldn’t believe that there could still be nothing wrong, but as far as my amateur eyes could see, the dog’s injured paw looked the same as the normal paw, which the vet had X-rayed for reference. How many lives does this dog have? I thought to myself.

Bromley has never been easy to love, so with the good news came relief, but also an enormous wave of shame. I know my job is to love this animal as long as she lives, but part of me hoped—honestly, guiltily hoped—that something was finally really wrong with her.

And somehow, Bromley knew. When we got home, she became strangely sweet. She started following me around the house, like she had something interesting to say but kept forgetting. She sat next to me if I was sitting on the floor—close enough that I could pet her, which wasn’t something she let us (or anyone else) do regularly. She didn’t stop drooling or snoring or peeing in the wrong places at the wrong times, but instead of the mean, reclusive cat we’d likened her to her whole life, she finally became a dog.

In return, we’ve started treating her like one. We’ve started petting her, because finally, she’ll let us. Last weekend, when Graham passed out in the middle of the living room floor, she took a nap next to him. And I actually cuddled with her. It took her five whole minutes to realize something unusual was happening and she stomped away.

And in the kitchen, we’ve simply kept spoiling her, because if a large dog can live almost 13 years eating all the human food dogs are supposed to avoid, a few more scraps on top of her pâté certainly won’t kill her.

Last night, we had spot prawns again, heaping piles of messy garlic- and chili-studded creatures on a platter for our own dinner. We sucked the sweet meat out of their shells, and heaped the tails and legs into a big metal bowl, which we passed on to Bromley on the back porch. She looked up at us in lucky disbelief, as if wondering whether perhaps they might be poisoned. We nodded and pushed the bowl closer. My husband and I hugged each other, somehow deciding, after 12-plus years, that we’d simply love Bromley the way she wanted to be loved. Because sometimes the sweetest thing you make isn’t what you eat, but what you don’t.

Spot Prawns with Garlic, Chilies, and Lemon

If you’re really going to do it right, eating spot prawns should be done with an apron on. That way, you can snap the tails off the creatures right as they come off the grill, slurp the juices off their legs (and out of their heads, if you’re so inclined), peel the shells off before dredging the tender, sweet meat in any lemony butter that remains on the plate, then wipe your hands on your front with reckless abandon.

In a pinch, whole fresh shrimp are a good substitute, but nothing beats the sweetness of spot prawns from the Pacific Northwest.

Serves 2 to 4.

1/2 cup (1 stick) unsalted butter

3 garlic cloves, finely chopped

1 teaspoon dried red chili flakes (or to taste)

1 medium lemon

1 pound fresh spot prawns

Preheat a gas or charcoal grill over medium-high heat (about 425 degrees F).

In a small saucepan, melt the butter over low heat. When the butter has melted completely, stir in the garlic and chili flakes. Zest the lemon and add that to the mixture, then slice what remains of the lemon into wedges and set aside.

Put the spot prawns in a large bowl and drizzle the butter mixture over the shellfish. Using your hands, scrape the leg side of the prawns against the bottom of the bowl, so each creature gathers up as much garlic as possible.

Grill the prawns for 1 minute per side, with the lid closed as much as possible, or until the prawns turn a deeper shade of pink and curl. (You want them cooked, but just barely.) Transfer the hot prawns to a platter, and serve piping hot, with the lemons for squeezing over them.

39 Comments

Filed under Buddies, commentary, dog, gluten-free, husband, recipe, shellfish

Tagged as here and now, northwest prawns, spot prawns, When to put down your dog